I was fortunate to take part in the Steering group meeting for the Road map, on October 17th-19th 2022, in World Health Organisation (WHO) Headquarters, Geneva. ASPHER has been working with the Global Network for Academic Public Health (GNAPH) and the WHO Health Workforce department moving forward a Road map for developing national workforce capacity to implement the essential public health functions including a focus on emergency preparedness and response. (1) The report was published ahead of the World Health Assembly on May 18th, 2022. It is intended to inform discussions of the International Negotiating Body (INB) of the Pandemic Preparedness Treaty, working its way through to the World Health Assembly, with planned approval by May 2024. (2) ASPHER has contributed to the developing ideas of this roadmap, those which have appeared in the last three years are set out in the text box number 1.

I was fortunate to take part in the Steering group meeting for the Road map, on October 17th-19th 2022, in World Health Organisation (WHO) Headquarters, Geneva. ASPHER has been working with the Global Network for Academic Public Health (GNAPH) and the WHO Health Workforce department moving forward a Road map for developing national workforce capacity to implement the essential public health functions including a focus on emergency preparedness and response. (1) The report was published ahead of the World Health Assembly on May 18th, 2022. It is intended to inform discussions of the International Negotiating Body (INB) of the Pandemic Preparedness Treaty, working its way through to the World Health Assembly, with planned approval by May 2024. (2) ASPHER has contributed to the developing ideas of this roadmap, those which have appeared in the last three years are set out in the text box number 1.

Box 1 Key ASPHER/GNAPH documents supporting capacity building in public health

The WHO Road map is complemented by several other key documents ASPHER has produced with European partners, on workforce development and competences:

- the WHO-ASPHER Competency Framework for the Public Health Workforce in the European region. (3)

- the WHO-ASPHER Roadmap to professionalizing the public health workforce in the European Region. (4)

- the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) Core competencies in applied infectious disease epidemiology in Europe. (5)

- ASPHER coordinates the Sharing European Educational Experience in Public Health for Israel (SEEEPHI) a Capacity Building in Higher Education project funded through ERASMUS+, which transfers knowledge and best practices from European Union Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to countries and HEIs outside the EU. (6)

In addition, the Global Network for Academic Public Health (GNAPH) has produced a strongly supportive statement: Global Governance for Improved Human, Animal, and Planetary Health: The Essential Role of Schools and Programs of Public Health. (7)

The meeting was helpful in giving clarity to some of the objectives needed if all countries are to achieve a higher level of assurance against new public health threats, and to enable them to commit to the wider goals of improving the health of the people they serve, in the context of a need for a One Health and Planetary Health approach. The meeting also marked the launch of an action plan for concerted action by countries through to mid 2024. (8) These are some of my observations made during the meeting, on the need for an expert and well-resourced public health profession. The reflections are in 2 parts – covering essential public health functions and professionalization of public health.

What makes up ‘public health’?

There are many definitions of public health: the one I use is from the English Acheson report of 1988. ‘Public health is the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through organised efforts of society.’ This is derived from Winslow’s 1920, definition used by many others since. (9) There are two common uses for the term ‘public health’. I find it helpful to talk about:

‘the public’s health’ or ‘the health of the public’;

and the public health system, service, and profession.

The health of the public is ‘everybody’s business’ – it requires a genuine partnership between community and health service interests, from policy to practice, it is multidisciplinary and intersectoral. A very long time ago WHO described ‘pre-requisites for health’ or ‘wider determinants of health’ peace, being more than the absence of war, clean water and sanitation, food, shelter, a healthy environment, adequate income, education, satisfying work, satisfying roles in society. (10) No-one group or profession can claim exclusive influence over all these determinants of health; genuine political and societal commitment is required to bring together policies and actions which protect and improve health. There must also be a public health specialist function as the catalyst for action and partnership on all these fronts. Without a dedicated expert overview of the health of the population, little is likely to happen to address major causes of ill health and to combat each major new threat that appears. That is why WHO and partners are placing so much emphasis on the need for action on national public health workforce capacity. (1,8)

REFLECTIONS FROM GENEVA, PART 1: ESSENTIAL PUBLIC HEALTH FUNCTIONS

The Road Map plan clarifies and crystallises actions required by governments and their health ministries. One small simplification it makes is in defining public health specialists as people who are involved in all the essential public health functions; it goes on to describe other public health workers, as those involved in one or more of the EPHFs. These roles are all vital to the functioning of the public health system and services.

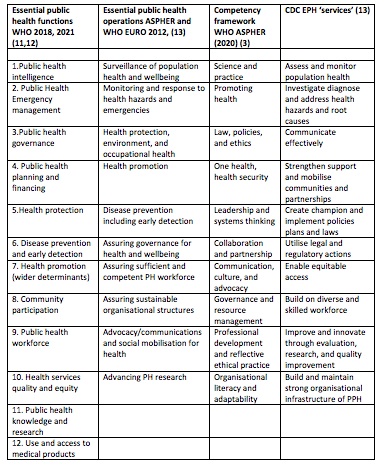

One big element we should all get behind is the identification of 12 Essential Public Health functions (EPHFs). There has been an extraordinary amount of work done over many years, defining EPHFs. For a long time, Europe has had 10 EPHFs, CDC Atlanta 10 and other regional groups of WHO various combinations of 8-11 (11) … During our discussions in Geneva, I tried to set out for myself, how some of these lists differ. I’ve set out my comparison at figure 1. WHO had done a first comparison, figure 2, comparing Europe, the Americas, Western Pacific and Eastern Mediterranean. (11)

Figure 1 & 2 some comparisons of essential public health operations/functions

There is considerable overlap in the various lists of essential public health functions, or ‘operations’, whatever we wish to call them. This is reassuring; it suggests everyone around the world has broadly the same view of what public health functions are required. The major addition in the latest WHO list, is the recognition of the public health role in relation to health services. Health care is not the least of our public health services; recognition of the need for equity of access, universal health care and measurement of the effectiveness and quality of health services are complementary and necessary concerns for better public health. There is a weakness in relation to communication, by comparison with some other lists- so that will need to be given strong expression in all the essential public health functions, and particularly in relation to community participation and public health governance. Ethical practice is also strong in the recent WHO-ASPHER competencies (3) for the public health workforce in the European region, so this will need to be described in the public health governance function. The WHO-ASPHER document (3) also has sub-functions well defined and split across ‘expert’, ‘proficient’ and ‘competent’, where these apply to individuals. I would strongly urge that these are looked at and borrowed extensively as they can also be applied to health system competencies.

Essential public health functions: In conclusion

Time is too short for us to have another indulgent round of attempting to come up with something better. Here, ‘the best is certainly the enemy of the good’. My conclusion is that we should run with the 12 Essential Public Health Functions set out in the Road map by WHO. (1) Nevertheless, if people are wedded to their own lists, that is fine and if they wish to stick by their lists, they should explain in their narrative why their version suits them. The differences in the lists are not enough to make for a big problem. So, my take home key messages are:

- Get behind the 12 WHO essential public health functions (1,11,12)

- Welcome the 2 explicit EPHFs relating to health and care: equitable access, and service quality measurement. These will need additional attention in devising sub-functions as they have not appeared in many EPHF lists previously. UK FPH curriculum may be helpful in this has ‘health care public health’ has been included for many years. (14)

- Give special consideration to issues of ethics and communications in the sub functions. WHO-ASPHER competency framework may be useful for this. (3)

- Give explicit recognition to One Health and Planetary Health in sub functions relating to Health protection and Emergency preparedness EPHFs. Again WHO -ASPHER framework relevant for sub functions.(3)

REFLECTIONS FROM GENEVA, PART 2: PROFESSIONALIZATION OF THE PUBLIC HEALTH WORKFORCE

The health of the public must be protected, by a body of professionals who are themselves regulated according to standards in education, in training and in their practice and service delivery. The public must be assured these people are what they say they are. The profession must be assured that their role and position will be valued, as long as they are committed to high standards of personal and professional conduct.

The WHO Road Map (1) helpfully describes Professionalization as ‘the process of giving an occupation or group professional qualities, typically through training and qualification. In the context of the public health workforce, this includes values and standards and an organizational structure that reinforces desirable behaviours and actions in the delivery of public health functions. Professionalization is the binding ethos within which the public health workforce needs to be developed. The WHO-ASPHER professionalization Road Map sets out the full theoretical basis and tools for professionalization. (4) Here are my summary 12 points on what makes for a public health profession.

My 12 points that make for a profession of public health:

- Is the need for a robust well-resourced public health system, service, function, and profession, expressed in local, national, or international policy statements? The vision, mission, policy, and strategy for protecting and improving the health of people and planet.

- Is there a statement of what knowledge and expertise professionals should have? Competencies

- And is it expressed in what Schools and Programmes should therefore teach? The Curriculum

- Do schools and programmes teach it to an acceptable standard? Accreditation

- Do graduates achieve the standard they have been taught? Qualifications

- Do graduates achieve a standard in relation to their practice and experience, as well as knowledge and expertise? Credentials

- Do professionals fit the requirements of their employers in the tasks they undertake? Job task analysis; Skills and knowledge frameworks

- Do professionals maintain their expertise? and practice to published standards? Continuing professional development; Public health (clinical) audit; and professional appraisal.

- Do professionals behave appropriately? Codes of conduct

- Are professionals supported in what they do? ‘Chambers’, ‘colleges’, ’associations’.

- Can professionals be removed if they do not maintain standards? And break codes of conduct? A Public Health Regulatory body

- Are professionals supported in their terms and conditions of work? Trade unions

Item 1 above is of particular significance, because it is essential to recognise clearly and explicitly why a public health workforce is needed, before going on to saying what it should look like. Culture, vision, mission, and values are prerequisites to designing a public health system and service which can deliver all the EPHFs.

It is tempting to seek to invest only in the immediate emergency public health workforce and technological fixes in epidemiology and infectious disease control. However, the pandemic has shown us that there are major issues for protecting health in vulnerable communities and patient groups, that there have been gross and widening inequalities in health and mortality, that there have been wide ranging societal needs including economic protection and housing. There has been a need to provide strong and trustworthy communications and combat the infodemic of disinformation. These wide-ranging impacts require a public health system which is multidisciplinary, versatile and adaptable; we must understand and use modern communications and social media, as well as being expert and in command of the science and knowledge. Long term gains for the public health were already being lost in years of austerity and in the face of eroded public health systems, so the ageing population of Europe and other industrialised societies was particularly ravaged. All these findings suggest that a reinforced public health system is needed, covering the full range of essential functions and competences.

In conclusion: The action plan for National workforce capacity to implement the essential public health functions including a focus on emergency preparedness and response

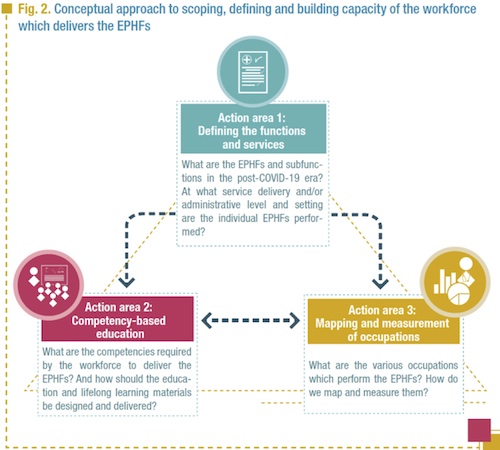

The plan has five workstreams overseeing the action plan through to 2024:

- Defining EPHFs subfunctions and services

- Competency based education

- Mapping and measurement of occupations

- Knowledge translation and dissemination

- General coordination

The first three are drawn from the schematic in the road map. (Figure 1- Figure 2 from the plan) Items 4 and 5 I would suggest are under the overall management of the WHO Health Workforce Unit and the Steering Group.

With colleagues in GNAPH we will seek to work with workstream leads, nominating representatives where needed. ASPHER professionalisation lead, Professor Kasia Czabanovska of Maastricht University will be a key resource for the working groups, on defining EPHFs subfunctions and services, competency-based education and mapping and measurement of occupations. This is an exciting action in support of better public health services and systems across the globe, but the window of opportunity is short, as politicians and decision makers start to look elsewhere, tiring of the COVID pandemic, even though it is still with us…. We welcome comments and views from ASPHER members.

References

- National workforce capacity to implement the essential public health functions including a focus on emergency preparedness and response: roadmap for aligning WHO and partner contributions. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240060364

- World Health Organization. Pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response accord. Geneva: World Health Organisation August 31st 2022. Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/pandemic-prevention--preparedness-and-response-accord

- WHO-ASPHER Competency Framework for the Public Health Workforce in the European region. Copenhagen and Brussels: World Health Organization and ASPHER, 2020. Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/444576/WHO-ASPHER-Public-Health-Workforce-Europe-eng.pdf

- World Health Organization European Office and Association of Schools of Public Health in the European Region (ASPHER) Roadmap to professionalizing the public health workforce in the European Region. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2022. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/351526

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Core competencies in applied infectious disease epidemiology in Europe. Stockholm: ECDC; 2022. ISBN 978-92-9498-570-5

doi: 10.2900/657328 available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/core-competencies-applied-infectious-disease-epidemiology-europe - Sharing European Educational Experience in Public Health for Israel (SEEEPHI): Harmonization, employability, leadership and outreach: Capacity Building in Higher Education for Public Health – A country case. Brussels: ASPHER Erasmus +outline, 2020. Available at: https://www.aspher.org/download/692/seeephi-project-profile.pdf

- Middleton J, Biberman D, Magana L, Saenz R, Low WY, Adongo P, Kolt GS and Surenthirakumaran R (2021) Global Governance for Improved Human, Animal, and Planetary Health: The Essential Role of Schools and Programs of Public Health. Public Health Rev 42:1604610. https://www.ssph-journal.org/articles/10.3389/phrs.2021.1604610/full

- National workforce capacity to implement the essential public health functions including a focus on emergency preparedness and response: action plan (2022–2024) for aligning WHO and partner contributions. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240060364

- London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. What is public health? London: LSHTM, 2022. Available at: https://www.futurelearn.com/info/courses/public-health-history/0/steps/30327

- WHO Declaration of Alma-Ata. International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6-12 September 1978. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/documents/almaata-declaration-en.pdf?sfvrsn=7b3c2167_2

- 21st century health challenges: can the essential public health functions make a difference? Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240038929

- Essential public health functions, health systems and health security: developing conceptual clarity and a WHO roadmap for action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/272597.

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Bjegovic-Mikanovic, Vesna, Czabanowska, Katarzyna, Flahault, Antoine. et al. (2014). Addressing needs in the public health workforce in Europe. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/332020

- UK Faculty of Public Health. Public Health speciality training curriculum. 2022. London: UK Faculty of Public Health Available at: https://www.fph.org.uk/media/3450/public-health-curriculum-v13.pdf