Author: Alejandro Gonzalez-Aquines1,2

1. Faculty of Health Studies, University of Bradford, Bradford, UK.

2. Institute of Public Health, Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland.

Contact information:

a.gonzalezaquines3@bradford.ac.uk

University of Bradford

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought unprecedented challenges to humanity. The virus, identified first in Wuhan, China, has impacted on countries in all forms of thought, from ensuring the supply of essential products in shops (e.g., food, toilet paper) to organising hospitals to provide care to a rising number of patients. The SARS-COV-2 virus was new, but corruption, a well-known problem in health systems, was to bring further challenges undermining countries' preparedness and response.

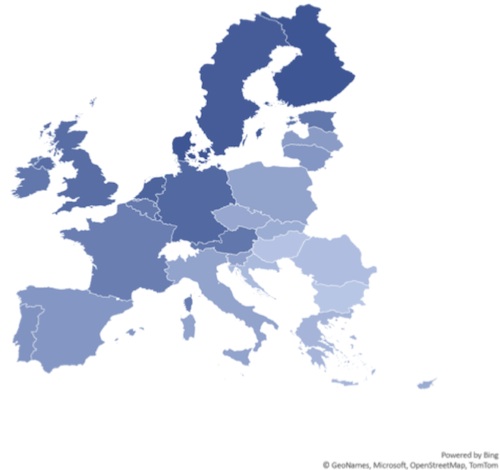

The European Commission defines six types of corruption: bribery in medical service delivery, procurement corruption, improper marketing relations and regulations, misuse of (high) level positions, undue reimbursement claims, and fraud and embezzlement of medicines and medical devices[i], the main type of corruption will vary across countries. The difference depends not only on the actors of the health system involved but also on contextual and historical differences, reflecting on the perception of corruption (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) in European Union countries and the UK. The darker the colour, the better performance and lower the corruption perception. Source: Produced by the author using the CPI 2021Transparency International data.

The pandemic continues to unfold with high numbers of cases in Europe and other regions, so countries must learn from the corruption cases emerging during the early stages of COVID-19, to implement actions to reduce the impact of corruption and be better prepared to respond to future shocks.

Identify the prevailing types of corruption in the country's health system.

There is evidence that health corruption is already widespread globally.[ii] Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic was another example of how countries see how the use of their resources is eroded. For instance, procurement corruption was more prevalent among Western European countries, as seen in the UK, where the government introduced a list of preferred providers to avoid going through a scrutinised procurement process despite not always being the best option.[iii] On the other hand, the misuse of (high) level positions was the primary type of corruption present during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in Central-Eastern European countries; for instance, in Slovakia, the Head of the Material Reserves was involved in a purchase of low-quality tests and received €200,000 in the form of bribery.[iv]

The examples illustrate that the who (who is involved?) and how (how is corruption taking place?) of corruption will vary from country to country, emphasising the need to implement monitoring systems in the healthcare sector to identify the multifaceted nature of corruption. Countries can rely on the types of corruption outlined by the European Commission as a starting point to categorise the most prevalent forms of corruption and develop strategies to tackle these.

Increase corruption monitoring systems during the months of shock.

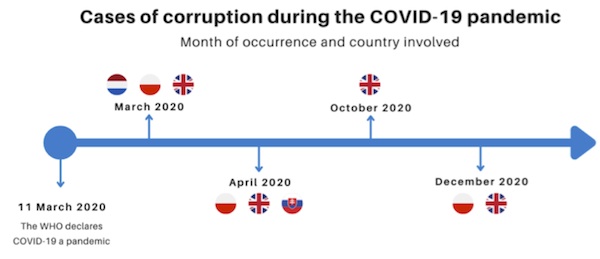

The first months of a shock come with uncertainty and a wave of critical questions: What should we do to protect the population? What resources should we acquire? Where should we get these resources, and how should they be distributed? A review of the literature (not yet published[v]) conducted one year after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic revealed that ten out of 13 cases of corruption identified in Western and Central-Eastern European countries occurred within the first three months of the beginning of the pandemic (Figure 2). However, instead of increasing the monitoring systems to prevent and detect actors engaging in corrupt practices, countries like the UK and Poland proposed policies that deterred the anti-corruption system's capacity.[vi]

Figure 2. Cases of corruption identified in selected Western and Central-Eastern European countries from March to December 2020. Source: Created by the author.

The uncertainty and increased vulnerability of health systems during the first months of the shock should be used by decision-makers to protect the country's resources. Implementing future preparedness and response strategies must include an element of corruption monitoring to avoid the inefficient use of resources that risk the population's health. Moreover, ensuring a comprehensive and effective plan to tackle corruption will reflect growth in public trust in the government. This element has been shown to be fundamental to increasing society's participation and adhering to public health recommendations during the shock.[vii]

Ensure safe mechanisms to report corruption.

Monitoring systems are crucial to tackling corruption in the healthcare sector; these should be implemented alongside policies and institutions protecting those reporting cases. European Union countries took a big step towards achieving protection for whistleblowers with the directive passed by EU Parliament in April 2019.[viii] The directive sets the minimum standards for countries to implement protection mechanisms for individuals reporting breaches in EU law, including engaging in acts related to public health. Among the support measures included in the EU Whistleblowing Directive are the independent, free, and comprehensive advice on their legal rights, remedies, and procedures; the effective assistance from regulators in their protection against retaliation, including providing certification to demonstrate that they qualify for protection; and the legal aid in criminal and cross-border civil proceedings.

The deadline for countries to implement the EU Whistleblowing Directive was 17 December 2021, but only nine of the 27 EU countries have adopted the law. Most of the Member States (17 out of 27) have started the process but delayed its implementation; Hungary remains the only country which has not initiated the transposition of the EU Directive into national legislation.[ix] The EU Commission has started infringement proceedings against the members delayed in the implementation of the directive, but the high number of countries exceeding the deadline to implement protection laws for whistleblowers raises alarming concerns about decision makers' priority to address corruption. Without safe mechanisms to report corruption, individuals will find themselves vulnerable, hindering them from informing about these practices and perpetuating the damaging effects of corruption on health systems.

Looking forward

Countries have started to prepare to deal with future shocks. Increasing the health workforce, enhancing primary care, and adopting digital technologies are among the strategies countries undertake to improve health systems' preparedness and response. However, it is utterly relevant that strategies aimed at improving the health system's performance include plans on how to prevent and identify corruption, particularly during the early stages of the shock. The COVID-19 pandemic has changed humanity in many ways; there should also be a change in how we view corruption and recognise that addressing it will foster better-prepared health systems, leading to healthier societies.

ASPHER editor's note

This blog piece is based on Alejandro Gonzales-Aquines’ prize winning Young Researchers’ Forum presentation at the Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland, Jubilee Conference, October 8th 2021. ASPHER encourages its young professional members to publish with the ASPHER blog.

[i] European Commission (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union). Study on Corruption in the Healthcare Sector; 2013. Report No. HOME/2011/ISEC/PR/047-A2. Available from: https://www.antykorupcja.gov.pl/download/4/12603/RaportKE.pdf [accessed 17 June 2022]

[ii] Hutchinson E, Balabanova D, McKee M. We need to talk about corruption in health systems. Int J Heal Policy Manag. 2019;8(4):191–4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2018.123

[iii] Investigation into government procurement during the COVID-19 pandemic. National Audit Office (NAO) Report [Internet]. Available from: https://www.nao.org.uk/report/government-procurement-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/ [accessed 16 June 2022]

[iv] Kajetána KiÄ?uru obvinili z korupcie, zasahovala u neho NAKA. Denník N [Internet]. Available from: https://dennikn.sk/1863356/u-byvaleho-sefa-statnych-hmotnych-rezerv-kicuru-zasahuje-naka/?ref=tit1 [accessed 16 June 2022]

[v] Gonzalez-Aquines A., Kowalska-Bobko I. Health corruption in selected Western and Central-Eastern European Countries during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed methods research. Master thesis. Available from: https://www.ap.uj.edu.pl/diplomas/150940/

[vi] Makowski G. The dangers of Poland’s proposed pandemic impunity law. Notes from Poland. Available from: https://notesfrompoland.com/2020/09/14/the-dangers-of-polands-proposed-pandemic-impunity-law/ [accessed 17 June 2022]

[vii] Han, Q., Zheng, B., Cristea, M., Agostini, M., Bélanger, J. J., Gützkow, B., Kreienkamp, J., PsyCorona Collaboration, & Leander, N. P. (2021). Trust in government regarding COVID-19 and its associations with preventive health behaviour and prosocial behaviour during the pandemic: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Psychological medicine, 1–11. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721001306

[viii] Protect Advice. (n.d.) EU Whistleblowing Directive. Available from: https://protect-advice.org.uk/eu-whistleblowing-directive/ [accessed 17 June 2022]

[ix] EU Whistleblowing Monitor (2022). Available from: https://www.whistleblowingmonitor.eu/ [accessed 17 June 2022]